Introduction

Greetings,

If you are following our social media pages you may have noticed we have been posting about some of the prominent and groundbreaking Black Americans in the legal profession to commemorate Black History Month. As we celebrate these nationally recognized pioneers in the fight for racial equity, we should also take time to remember the men and women, whose names and stories are less well known. It was these individuals who organized and performed the day-to-day work of the movement in their local communities.

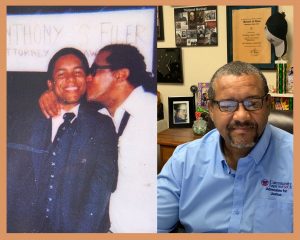

Last month, at our annual leadership team retreat, everyone in the group shared about their inspiration in their role here at CLA SoCal. Anthony Filer, the Directing Attorney for our Los Angeles County offices, shared about his father, who was one of the local heroes of the civil rights movement. He was an activist who dedicated his life to serving his community and it was his example that led Anthony to a career in legal services. I was so moved by his story and the images that Anthony shared so I asked him if he would be willing to share with the rest of our team. Thankfully, he agreed and so we are sharing the story below.

I hope you enjoy reading My Father as much as I did.

Warmly,

Kate Marr

Executive Director

My Father by Anthony Filer

I love it when someone asks me how I ended up being a public interest attorney. It gives me a chance to tell my father’s story. And not just the story about his persistence with taking the California Bar Exam, but the story of how he ended up wanting to be an attorney, and how that story got me where I am today.

Origin

My father was born in his family’s home in tiny Mariana, Arkansas. At the age of 14, he put his age up to 16, to join the army because it was either that or picking cotton. After serving in the army, he returned to Arkansas, but soon ended up in Elkhart, Indiana. He met my mother there and they started a family. Frustrated with the type of jobs he was able to get and tired of the cold winters, he decided he wanted to move to California.

The move west

They settled in Southeast Los Angeles and he decided to buy a house for his growing family—his wife and two children. When the realtor happened to stop by his own house in Compton while showing homes to my parents, my father indicated that he really liked the neighborhood. The realtor let him know, without hesitation, that Negros were not allowed to buy homes and live in that part of Compton, known as Henrietta Square (about 4 blocks from where the Compton CLA SoCal office is presently located). This interaction was my father’s induction into the Civil Rights Movement.

Without the assistance of the realtor, he proceeded to buy a home on the same block as the realtor, four houses down on the corner of Arbutus and Mathisen (my oldest sister still lives there). The year was 1954 and soon thereafter my parents were involved in everything and anything that dealt with civil rights and equal rights.

Awakened to activism

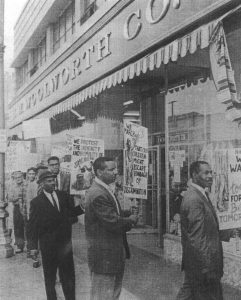

My father became a member of the Urban League and CORE (Congress on Racial Equality) and the President of the Young Democrats. He started and became President of the Compton Branch of the NAACP. Soon there were seven children in the family and our weekends consisted of Little League, Boy Scouts, dance classes, and walking picket lines with my father.

In 1963, my father traveled to Washington, D.C. with local Black politicians and civic leaders from Southern California. He carried the California flag at the March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Five years later, he carried the same flag at Dr. King’s funeral in Atlanta, Georgia, after he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee.

In 1965, during the Watts Riots, as we all slept in our living room on the floor, listening to the helicopters and gunshots going off all night, my father was on site in Watts begging the white business owners to not try to go and check on their businesses. When some would go there anyway and were attacked by the rioters, he would drive them out in their cars, while they hid in the back seat.

Standing up and speaking out for change

In 1966, after the Watts Riots, my father spoke before the McCone Commission to advocate for a hospital in Southeast Los Angeles County (my youngest brother bit through an old fashion cloth electrical cord and I can vividly remember the family driving from one local medical clinic and center to another with my brother in great pain and his face having an open wound and all of them saying they could not treat him). One of the results of the McCone Commission was the opening of MLK, Jr. Hospital.

In 1969 my father was the campaign manager for Douglas Dollarhide, who was elected as the first African American mayor of the City of Compton, and the first African American mayor of a major municipality in the State of California.

The law, a vehicle for change

When my father realized that it was the attorneys, the Civil Rights lawyers like Thurgood Marshall, who were having the greatest impact on producing change in our systems and institutions, he decided to go to law school. While raising seven children, working two jobs, and still staying as active as ever in the Civil Rights movement, he finished law school. But he couldn’t pass that doggone Bar Exam. He took it every time it was offered, and while taking it continued to work two jobs, served on the City of Compton Personnel Commission, the Compton Community College Personnel Board and finally the Compton City Council.

On the forefront, a first for gun control

While a council person, he wrote the first municipal ordinance in the State of California that banned the sale and possession of assault rifles. That one got us threatening calls on our home phone from NRA members from around the United States, the first one from New York came on the same night the ordinance passed.

When filmmakers came to the City of Compton to do a documentary on NWA and gangster rap and they were talking about the colors of the different gangs, they included a clip of my father saying, “the only color these thugs cared about was the color green (as in money)”. In response, Ice Cube laughed and said he was right.

Persistence pays off

In case you didn’t know, in 1991, after he had done all of the things mentioned above, along with being involved in so many other parts of the Civil Rights movement in California and especially Compton, raising seven children and instilling in them their commitment to give back to the community, and after serving on the Compton City Council for 15 years, he passed the California Bar, 24 years after he started taking it. Most of the big Civil Rights cases had already been decided in the courts, but my father got to walk to his office and practice law on Compton Boulevard for almost 20 years, which in the end is what he said he always wanted to do.

Serendipitous connection